The Reasons for and Responses to Police Misconduct

Wake Forest Law Experts Weigh in on the Tyre Nichols Case

At the end of January, Memphis authorities released footage of police officers severely beating Tyre Nichols, who was pulled over for alleged reckless driving. Nichols died in the hospital three days after the altercation. The public has quickly organized, protesting the killing of yet another unarmed Black man at the hands of the police.

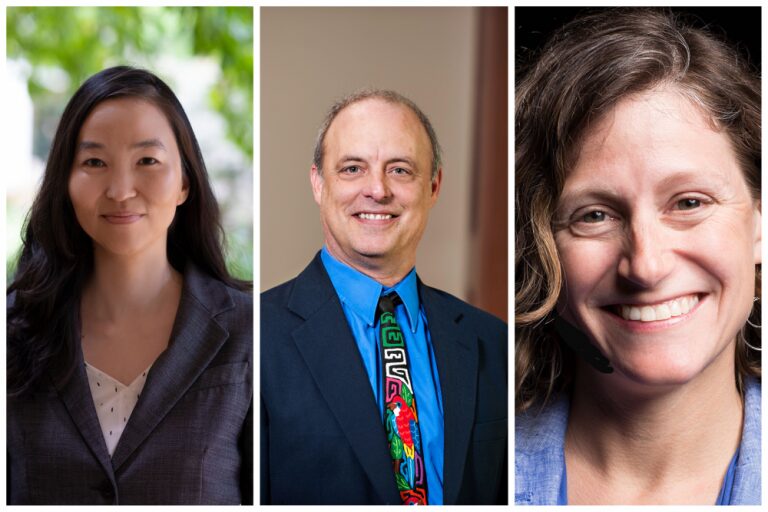

While there have been countless think pieces written about the Nichols’ case already, Wake Forest Law faculty members, experts on criminal justice and the carceral system, share their perspectives.

Professor Alyse Bertenthal teaches criminal procedure, focusing especially on constitutional limitations on police investigations, including those involving the use of force. “But what happened to Tyre Nichols can’t be explained only as a failure of law,” Bertenthal says. Her research examines the cultural constructions of crime and crime control and, she explains, “We have to be attuned to the social, structural, and institutional dynamics that generate such tragic consequences for Tyre Nichols and too many others.”

Among those dynamics are the prevalence of racial disparities in the criminal justice system. Black adults are arrested at a rate 5 times higher than white adults. This disparity even holds true for youth. Professor Esther Hong’s work focuses on youth and emerging adults in the juvenile legal system and the criminal legal system, and the comparison between these two carceral systems. She says, “While total youth arrests have substantially decreased in recent years, there are still racial disparities in arrests. Black youth are more likely to be arrested than white youth. These disparities manifest in punishment too—the Black youth incarceration rate is approximately 4 times that of white youth.” Although Nichols was 29 at the time of his killing, it is important to understand the larger cultural context of the pervasiveness of arrests within the Black community.

Professor Ronald Wright, one of the nation’s best known criminal justice scholars whose research concentrates on the work of criminal prosecutors, discusses the response from legal institutions.

“When events like this happen, remedies might come from within the police department, from criminal charges against officers, civil torts suits against the officers and the city, or restructuring of the entire agency,” says Wright. “The comprehensive legal actions of this network of legal actors remind us that the answer to illegal use of force by the police is not the work of one person or one department, but rather that of the whole system.”

Over time, responses have become more reliable and robust. If you compare police brutality events from 5 years ago to the Memphis event, responses are now faster and more transparent. Memphis officials released the video within days, which gave people more confidence that legal actors would respond seriously and carefully. Officials from city governments across the country now proactively develop plans for the steps to take if police officers use unlawful force. Significant thought is being put into how to react to these situations.

Are these efforts actually effective deterrents to deadly police misconduct? It’s practically impossible to tell.

“With 17,000 different policing agencies in this country that have no infrastructure for centralized data collection, we have only a glimmer of how often the police kill someone, how often that victim is unarmed, the nature of the victim’s underlying conduct, and other factors,” says Wright. Wright is teaching a new seminar this spring semester on policing, developed in response to student interest in ways that the law can reduce police misconduct. “In any other country in the world, there is a national hierarchy of police and centralized data. Decisions around use of force are made at the top levels and then become the rule for all policing organizations within that hierarchy. But not in the United States.”

Policing in this country is so decentralized because we as a nation have always treated public safety and the police power as local matters—primarily because conditions and crime from city to city are so varied. This localized approach was once true of the courts and prosecution as well, but in the middle of the 20th century, control of the courts and prosecutors shifted from the local to the state level. Yet policing agencies remained under the purview of local governments and continue to do so today. Classic political theory says that local control is most effective at preventing abuses because people can monitor government activities more closely. But this results in a fragmented system where agencies are unable to share information. Thus their ability to fix systemic problems is limited. In the case of Tyre Nichols, local control of the police hasn’t actually been an effective way to stop misconduct.

“To be serious about stopping police brutality, we must keep closer track of what happened in a given situation and why,” says Wright. “The Memphis police department must share its data, which could then be added to a nationalized database that would allow for us to see patterns and intervene.”

Often, the debate around policing is framed in terms of law enforcement effectiveness standing in opposition to acting fairly, but according to Wright, “There doesn’t have to be this tradeoff.” When law enforcement breaks the trust of the community by not acting in a lawful and trustworthy manner, it can no longer rely on the community to help police solve crimes and keep people safe. Police brutality not only has an irrevocable and devastating impact on the lives of those directly touched by it, like the Nichols family, but also damages the relationship between law enforcement and the community, rendering the police ineffective, or even toxic.

While it will surely take a long time for the people of Memphis to regain trust in law enforcement, the rapid and thorough response can only help the process. “The legal system is in place to ensure that what happened to Tyre Nichols doesn’t go unanswered,” says Wright. “If the law is here for anything, it’s for this.”

Categories: Our People